“One artist was not really enough,” says Linda Kitson (b.1945) when speaking about her time in the Falklands. “If there was a quorum around me, [...] we would have gotten a much bigger picture of all the extraordinary things that were happening over such a short period of time.”

The Falklands War lasted just seventy-four days. Despite its relative shortness, the conflict resulted in the deaths of nearly one thousand men. At the centre of it all lay a messy history. The Argentines were fighting for the islands – while the British were fighting for the Islanders. It was a complicated war where the question of who the invaders were did not seem to have a particularly simple answer. To the Argentines, it was an opportunity to reclaim a history and heritage that they felt was rightfully theirs; for the British, the attack was seen as an unjust assault on British citizens that could not go unpunished. The Falklands War was a dark and tragic chapter in the history of the islands – and it stood as a sharp reminder that the scars of colonialism were not easily healed.

On May 12, 1982, Linda Kitson departed Southampton port on the recently requisitioned QE2. There, she was virtually the only woman on board, travelling with three-thousand men on a fourteen-day journey that took her thirteen-thousand kilometres away from home. Her assignment had come as a commission from the Artistic Records Committee of the Imperial War Museum – making her the first officially commissioned female war artist.

At this point in her career, Kitson had already established a strong reputation for creating reportage illustration. She had already documented a number of impressive events, including a behind-the-scenes look at life at The Times – as well as creating a series of drawings to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the BBC.

For this particular task, Kitson knew that the commission would offer her something unique. “I knew that [it] would give me the chance to see and experience new drawing opportunities,” she wrote in the introduction to her Falklands Visual Diary (1982). She also believed that the commission might help her to serve something outside of herself. “[Illustrators] work alone a great deal" she noted, "and it is easy to become introspective [...] I hoped that by working among thousands of troops, something would emerge.”

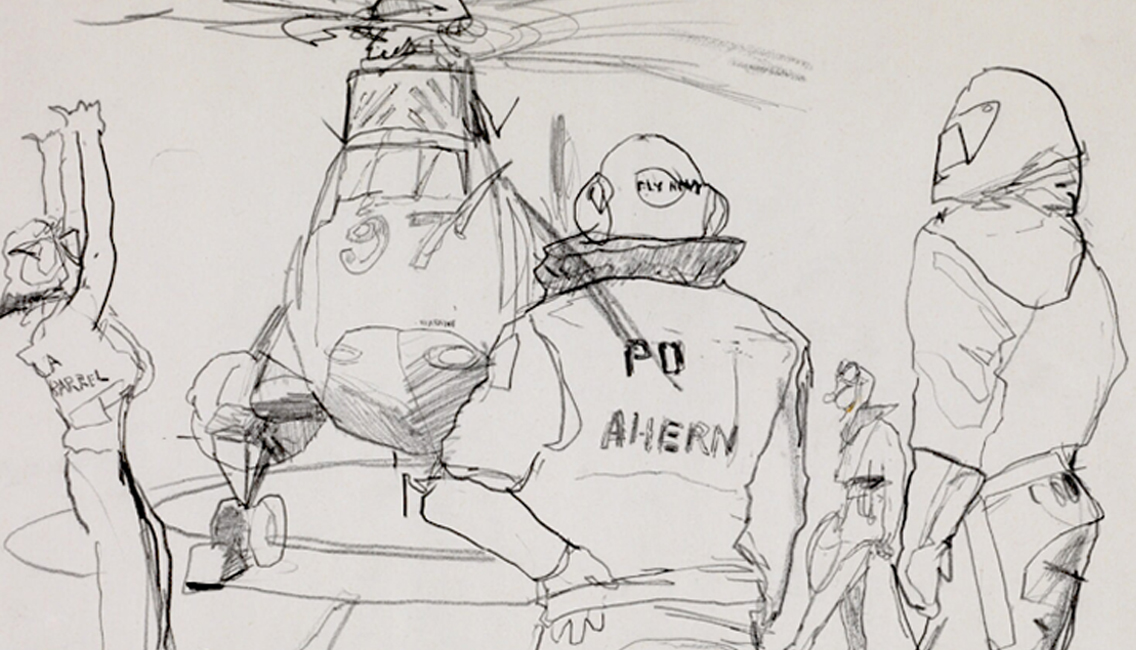

Onboard the QE2 Kitson wasted no time – producing one-hundred drawings in only a handful of days. These drawings show an intimate record of life on board and let us glimpse the preparations that were undertaken on this newly repurposed naval vessel. Kitson was told that she could draw whatever she wanted and whatever she found interesting. Her images from the journey show us drill exercises, scenes from the flight deck, meetings in the information room and plenty more. At South Georgia, she transferred with the troops onto the SS Canberra and eventually was deployed at San Carlos.

Once on land, there was little time for anything other than the job in hand. Operating with a number of units, Kitson moved between parties by helicopter – drawing constantly. In addition to the ever-present risk of attack, conditions in the Falklands also posed a sizeable threat. Cold weather caused hypothermia, trench foot and frostbite, and the freezing conditions frequently made drawing a near-impossible activity. “The business of drawing in such a hostile climate was terrifying” she recalled.“You lost contact with your hands.”

Despite not often being able to feel what she drew, Kitson persevered – and continued to draw everything that she saw. Her greatest skill lay in her ability to translate huge pieces of visual information onto paper at a lightning-fast speed.

During her time on assignment, she produced roughly six drawings a day – typically using a combination of pen-and-ink, pencil and conté crayon. These illustrations are simple and are articulate – immediate and yet intimate. Unlike a journalist, photographer or camera crew – Kitson's marks don't tend to seek out sensationalist or dramatic moments. Instead, her work tends to focus on showing how people exist within their surroundings and the experiences that they might have shared together. These are unromantic scenes – images that form an authentic and distinctive portrait of the conflict.

Throughout her career, Kitson has always been keen to maintain that what she does is not journalism or reportage – instead, she prefers to describe it as being a 'witness'. These are unique pictures of what she saw; and – perhaps more importantly – what she experienced. In many ways, they present a subjective view – something that stands in contrast to the objective way in which war often tries to present itself.

In an interview with the BBC, the illustrator discussed how her work was never censored, but that she realised that she often censored herself. “I didn’t draw body bags, I didn’t draw the burnt,” she said. In Kitson's drawings, the dead and injured remain noticeably absent. This was a conscious choice. “I had to make a decision about what aspects of war I should record,” she wrote. Out of sensitivity to the victims, she decided that such horrifying scenes were not part of her brief. “I wouldn't do it even now” she noted, “and therefore I'm very different to the news, and very different to anything that's dispassionate.”

Like all modern war artists, Kitson stayed a couple of days behind the action, yet the threat of attack was still always present. All but one of the battles on the Falkland Islands had taken place at night, so even if Kitson had been at the heart of the action there would have been little for her to draw. Instead, her illustrations follow the destructive path of the war. Many of her images present a haunting record of past events – the moored Sir Galahad burning in flames, the recovering soldiers at Fitzroy's field ambulance, the destroyed Pucarás at Stanley airstrip. There are no shock tactics here, just a grim reminder of the reality seen in the aftermath of battle.

On June 14, Argentina surrendered, and British control was returned to the islands. It took twenty-eight days for Britain to officially declare that the war was over. Capturing that moment proved a challenge. “It was impossible to capture any real detail on paper,” she wrote, “so many of the main protagonists never stood still for a minute”.

The Falklands War was a conflict based on pride and nationalism, and its outcome came at a heavy cost. During her sixty-six days in action, Kitson drew continuously. Despite the cold and exhaustion, she produced over four hundred drawings. These works offer us a brief glimpse into a dark chapter of recent history and provide us with a sense of what it must have been like to be a soldier on active service during the war. Let us hope that they also act as a reminder that such conflicts should never happen again…

You can find details on where to purchase or borrow The Falklands War: A Visual Diary here.

Where next?

If you found this essay interesting, you might also enjoy exploring these selections:

Women Artists And War

While the job of documenting war has – traditionally – been thought of as a male preserve, this understanding is a falsehood. Many female artists and illustrators have played a crucial role in depicting conflicts; amongst them are people like Elizabeth Thompson (1846–1933), Gertrude Leese (1870–1963), Laura Knight (1877–1970), Anna Airy (1882–1964), Evelyn Dunbar (1906–1960), Mary Kessel (1914–1977) and Arabella Dorman (b.1975).

Other Commissions by the Imperial War Museum

The IWM has a long tradition of commissioning artists to create work that reflects recent and contemporary conflicts. Previous artists have included the likes of Paul Seawright (b.1965), Roderick Buchanan (b.1965) and Steve McQueen (b.1969).

Will Kevans' Falklands War Comic

In 2014, the cartoonist and songwriter Will Kevans self-published a graphic novel that chronicled his time as a Welsh Guardsman serving in the Falklands War. My Life in Pieces provides a unique and poignant glimpse into the trials, horrors and humanity that he saw during his time at war.