If you're looking for a who's who of Victorian life, then grabbing an old copy of Vanity Fair is a good place to start. The most successful 'Society Magazine' in the history of English journalism, the publication ran under the promise of presenting “a weekly show of Political, Social and Literary Wares”. For almost fifty years, it invited readers to recognise their vanities and, each week, it would summarise world events, review West End shows and — most importantly — caricature its readers. From artists and authors to scholars and statesmen — the Vanity Fair caricature was an integral part of upper-class Victorian life.

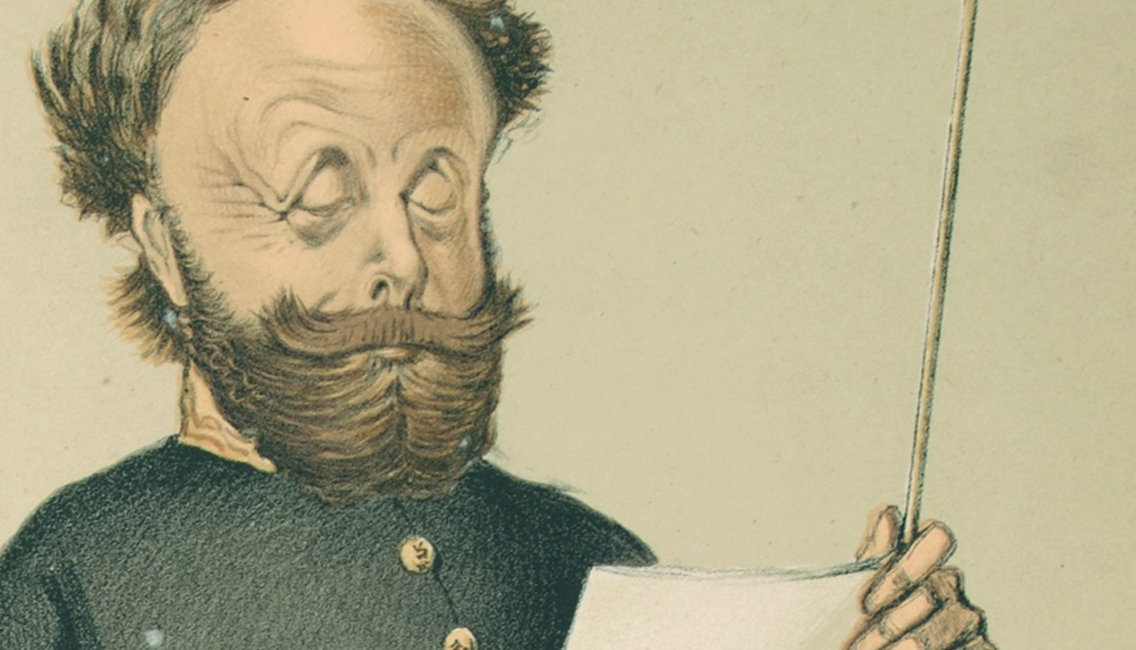

The most prolific caricaturist at the magazine was undoubtedly Leslie 'Spy' Ward (1851–1922). From 1873 until 1911, Spy captured the people and personalities of Victorian society. During his time at the magazine, he produced more than half of its 2,387 caricatures and documented the best-known figures of the day. His work was immensely popular, and he was largely responsible for reviving the tradition of the single figure caricature.

These days, these types of drawings may feel like a bit of an oddity — they tend to lack the satirical edge we think of when we first think of caricatures. Yet despite this, Spy was undoubtedly one of the best of his era. His images may feel more complementary than insulting, but this is very telling of the time in which they were made.

For Spy, satire lay “not in any personal venom, but in the artist's detached observation of life and character”. His images present an amazing record of the era, and he was well aware of this even during the time he was making them.

In his 1915 autobiography — Forty Years of 'Spy' — he wrote: “I venture to prophesy that, when the history of the Victorian Era comes to be written in true perspective, the most faithful mirror and record of representative men and the spirit of their times will be sought and found in Vanity Fair.”

Spy's era was that of the Victorian Empire. While we may have spoken already at some length about this period, it is not something that can easily be ignored. The Victorians played a huge role in shaping many aspects of Western culture, and the social factors behind these developments are hugely relevant when looking at the context of anything that was created during that time. The era was defined by huge class divides. It was a time of reputations and an era where respectability meant everything. Undoubtedly, these factors shaped the world of illustration too.

Fortunately for Spy, the illustrator was born into the right kind of family for living a successful Victorian life. Both his parents were respected artists, and he quickly learnt how to mix in the right social circles. He studied at Eton and attended all the right clubs. In no time at all, he was a staff member at Vanity Fair, sharing caricature duties with Carlo 'Ape' Pellegrini (1839–1889).

Spy's early caricatures were closer to the types of satirical caricatures we think of today. They have distorted proportions — large heads and exaggerated features. Yet the longer he stayed at the magazine, the more his reputation grew. Over the course of his career, his style developed, moving further away from caricature and turning more into what he described as 'characteristic portraits'.

These conventional interpretations brought him great acclaim, and his sustained productivity brought him great popularity. He might not have had the originality, or artistic talents, of some of his contemporaries, but his strong work ethic was worthy enough to justify his success. In 1918 he received a knighthood to highlight his 'good work to the citizens of the British Empire'.

Today Spy and Vanity Fair offer us a unique window into a special part of British history. The magazine charted this period with style and panache. Yet, it wasn't a time that could last forever. On the 5th of February 1914, Vanity Fair published its final issue. Five months later, Britain was to find itself in the trenches of Europe. As the magazine faded into the annals of time, so too did the society it charted. The Victorian Era was over, and with it went a very particular type of illustration.

Where next?

If you found this essay interesting, you might also enjoy exploring these selections:

André Gill's caricatures in L'Éclipse

If Spy and Vanity Fair are considered inseparable, then the same could be said for André Gill (1840–1885) and L'Éclipse. First published In 1868, the French magazine was the perfect showcase for the illustrator's talents.

Alfred Bryan in Entr'acte

Alfred Bryan (1852–1899) was a popular English illustrator and was a contemporary of Ward's. He is best known for his contributions to the London-based weekly theatrical review Entr'acte.

Harry Furniss in Punch

A British illustrator born in Ireland, Furniss (1854–1925) was also a contemporary of Ward's. While Ward's caricatures were overly sympathetic, Furniss' were far more scathing. He is best known for his work with The Illustrated London News and Punch.