The former editor of Punch Magazine, Malcolm Muggeridge (1903–1999), once remarked that “Life holds no more wretched occupation than trying to make the English laugh”. From self-deprecation and sarcasm to innuendo and absurdity, English humour has always stood out as unique. But what are the factors in society that lead to this type of humour? How can experiences, opinions or backgrounds shape what we define as funny? What is it that makes the English laugh?

Last time on Illustration Chronicles, we witnessed the birth of Punch Magazine, introduced the work of illustrator John Leech and saw the world's first political cartoon. This time we're going to broaden things out a little. We will stay in England for now, but we'll take a little more time to examine the country during the 1800s and hopefully learn a little more about the society that helped shape a sizeable portion of the visual language within western illustration.

In the introduction to this topic, I said that satirists have a moral calling and emphasised that their role stems from a desire to highlight the hypocrisies of a time. Well, the Victorian Era (1837–1901) certainly had its fair share of hypocrisy and the period can easily be defined as one of contradiction and changing standards.

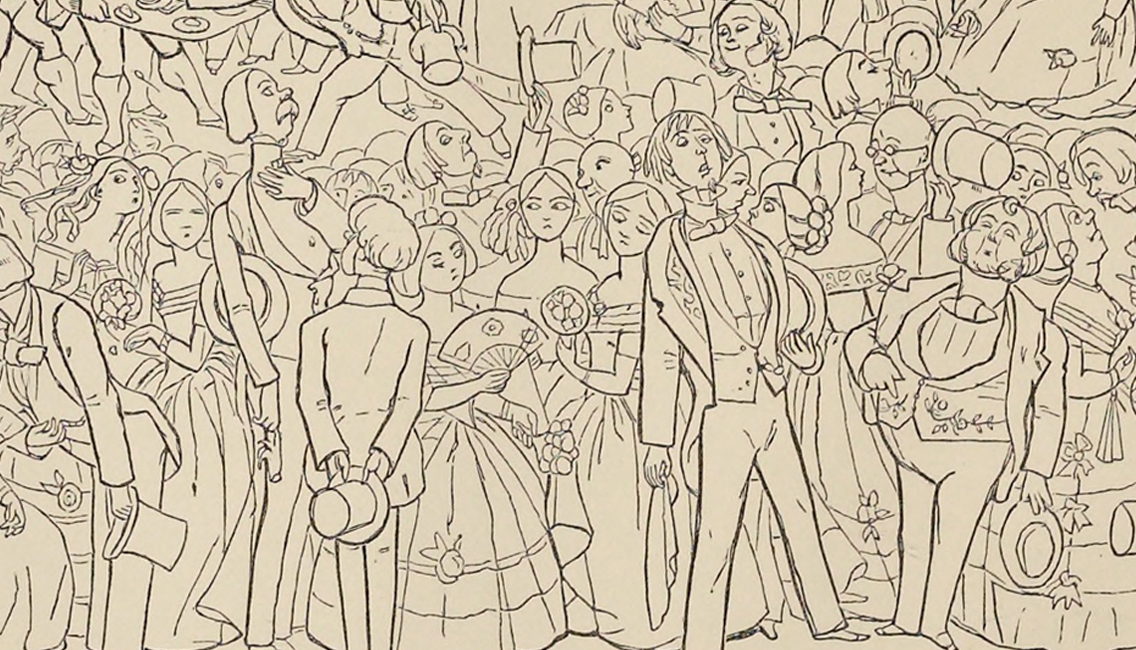

Throughout this piece, I will feature work from The Manners and Customs of Ye Englyshe by Richard “Dicky” Doyle (1824–1883). Its title, 'Manners and Customs', parodies a style of travel book was popular at the time — with Doyle's work playfully looking inwards where these titles tended to look outwards. First published in 1849, it is a compendium of cartoons that had initially appeared as a series in the pages of Punch.

The cartoons mock the foibles and fashions of English society and, while their target is the bourgeoisie, their humour is arch and mild-mannered. As a modern reader, it might be easy to feel that these images should be more antagonistic or provocative yet, in many ways, they are emblematic of the amiable satire that was being produced during this period. Doyle was well aware of the hypocrisy of his time (see, for example, the poor small boy huddled outside the shop in the top-left corner of the illustration below). Yet his typical approach is to utilise this hypocrisy for playful social satires rather than any pointed political statement.

A good example of this can be seen in the image below that illustrates a lively 'at home' Polka. Here we have a servant accidentally being punched in the face, a lady about to be crushed by her suitor, and a gentleman whose tailcoat is moments away from catching fire. It's a lively scene, yet it's still rather polite. It highlights the trivialities of middle class life and mildly mocks the Victorian ideals of dignity and restraint. In most regards, it is a cartoon about the Victorians — for the Victorians.

Doyle's work also shows us the world of Victorian wealth. In 'A Few Friends To Tea and a Lyttle Mvsyck' [sic] he playfully mocks the lavish efforts that people went to so as to appear wealthy, well-educated and cultured. At the start of the Victorian Era, the elite were in total control of society and politics. Made up of about 300 families, this ruling class slowly began to share power with a newly emerging middle class. Reform Acts throughout the era extended voting rights to previously disfranchised citizens, and new values began to emerge. Despite a rather rigid class system, the idea of a 'self-made man' was a common aspiration for the middle classes, and people felt that they could become wealthy through stoicism and a strong work ethic.

Yet, the typical middle class Victorian needed more than just wealth to be taken seriously. As the middle classes grew in size, a person's social standing played a significant role in their sense of self. Respectability was just as important as wealth to a middle class Victorian and this was something they cultivated to ensure that they were distinguished from the lower classes. Literacy was on the rise, and people had more leisure time to pursue an interest in the arts. Galleries, theatres and music halls were all popular places to be seen, and an interest in these pursuits brought great respect and admiration.

As a reaction to modern developments during the era, the Victorians were frequently inspired by the past. During this time, we see movements emerge like Gothic Revivalism and the Pre-Raphaelites. Within the art of illustration, Victorians were developing a fondness for Germanic prints. Doyle hated this antiquated approach to the discipline and was keen to ridicule its appropriation. In Manners and Customs, he directly parodies the style of Moritz Retzsch (1779-1857). Retzach's work was filled with brilliant scholars and valiant heroes but in Doyle's work, these are replaced with the bumbling bourgeoisie. It's a sly attack on the solemn pretensions of the time.

As well as a passion for culture, respectability came from good manners. Being dignified and proper was of the utmost importance when being in society, and people took great satisfaction in appearing to hold wholesome middle class values. Conforming to the values of the Christian faith was important, and the Victorians took pride in how they would like the world to be. To them, they were the pinnacle of humankind. The British Empire was at its height, with Victoria ruling over more than a quarter of the world's population. The technological advances brought on by the industrial revolution also brought immense progress. In 1849 — when this book was published — its illustrator would have had lived through the birth of intercity rail (1830), the first photograph (1835), and the first telegram (1844). It was an incredible period for change.

Yet despite all this progress, there was still immense poverty and injustice. In 1849 two thousand people a week died of cholera, and — in Ireland — the Great Famine raged (1845–1852). Doyle was someone who greatly valued his Irish ancestry (his father was the prominent Irish illustrator John Doyle). In these terms, it is not hard to imagine that he took real issue with the superficial gloss of middle class manners and customs.

For Doyle, this all came to a head the following year. The Victorians held religion in high regard — subscribing to a strong Protestant work ethic and holding deep Christian values. Yet, despite this, a strong anti-Catholic attitude persisted throughout the nineteenth century. With Irish migration to England rising on account of the famine, this sentiment continued to increase. Rome was keen to reinstate its hierarchy, but this led to many cries of “no popery” (illustrated in both images below). Punch Magazine took a strong anti-Catholic line and campaigned strongly against the Pope. This was too much for Doyle who resigned from the magazine in November of 1850.

Doyle had spent seven years at Punch. He had joined in 1843, aged just nineteen. During his time there, he shared illustration duties with John Leech, and together they helped define the magazine's identity. His intricately designed Punch masthead helped to establish the magazine's tone for mockery and irreverence. It mixed fairies, twigs and elves, and was used at the magazine for well over a century. Doyle had always had an interest in fairies and after his resignation, he had more time to peruse this passion. While he still continued to work within satire (his impressive Bird's Eye Views of Society is a noteworthy example), his fairy books brought him most of his recognition. His beautifully produced In Fairyland, a series of Pictures from the Elf World (1869-70) is an absolute masterpiece and a perfect example of the Victorian book.

Unfortunately, Doyle's twin passions of fairies and satire never crossed over. It's not hard to envision that his escape to Fairyland worked as a way to escape the absurdities of Victorian life. Yet, despite Doyle never mixing the mythical with the satirical, there are examples of where these two elements do come together. To see this, we will need to leave England behind and head east. This will be our next stop on Illustration Chronicles and will involve an encounter with one of the craziest illustrators to ever emerge from nineteenth-century Japan…

Where next?

If you found this essay interesting, you might also enjoy exploring these selections:

The Victorian Web

If you're interested in the Victorians, I found the Victorian Web to be an amazing resource when writing this piece. Filled with a wide range of Victorian topics (including illustration) it comes highly recommended.

Hablot Knight Browne's illustrations for David Copperfield

Manners and Customs was released the same year as Charles Dickens' David Copperfield. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne (1815–1882), the book provides a great look into Victorian life.

'The Man Who…' series by H. M. Bateman

Another Punch regular, Bateman's (1887–1970) 'The Man Who…' series pokes fun at the social gaffes of the upper class with great humour and wonderful drawings.