If you try to think of the work of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901) and then try to imagine life in Paris in the late nineteenth century, you'll quickly realise that the two are almost inseparable. His illustrations pour from the page with all the sensuality, bohemianism and decadence of the era. His scenes of Parisian nightlife depict famous late-night bars, rowdy dance halls, bustling cafés and exuberant circuses. Looking through his collection of posters, drawings and paintings, you can almost taste the absinthe on your lips or smell the heady mix of cigarettes and coffee.

Lautrec lived in Paris during the Belle Époque and was a friend to Manet, Degas, Gauguin and van Gogh. In terms of global influence, the city was arguably the cultural centre of the world. It was a time of revolutionary literature, music, theatre and art. It was a period of unbridled optimism and positivity, decadence and depravity. The industrial revolution had come and gone and, in its wake, was left a new generation of middle-class people eager to explore new pursuits and pleasures.

From this, a new leisure culture emerged, and this heralded a new era for advertising. Large format lithographic prints sold goods and entertainment, and illustrators eagerly worked hard to grab the public's attention. By the 1890s, poster art was in its infancy, but it did not take long for these illustrated works to gain popularity. What emerged was a golden age for the discipline, and posters quickly turned from disposable frivolities into well-regarded art forms.

In 1891 Lautrec created his very first poster and, in the process, he became an overnight success. Three-thousand of his lithographs spread quickly through the streets Paris — captivating the city with their bold use of colour, brash design and playful innovation. In terms of printmaking, it was a revelation. His image stood in brazen contrast to the text-dominated posters that were typical of the time. Within days, it had become a collector's item, and it established the illustrator's reputation as a champion for the pleasurable and disreputable.

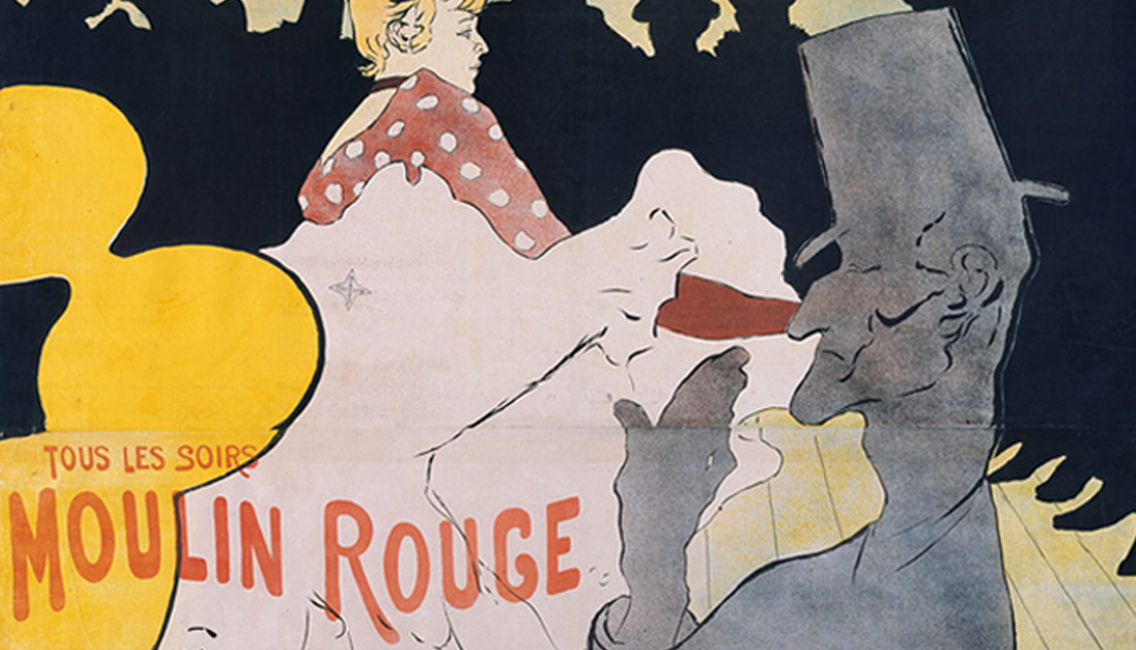

Inspired partly by Japanese artwork and printed as a four-colour lithograph, the poster advertised the dance hall of Montmartre's Moulin Rouge. The club had been open for just two years, and it played host to inventive cabarets, new forms of dance, lively concerts, extravagant circus-inspired shows and festive champagne evenings. Lautrec captured the raucous energy of the venue with a glee that could only have come from his personal devotion to the venue.

Looking at his poster (above), we can clearly see a group of spectators gathered around the main dance floor. Modern yellow electric chandeliers liven up the image while a lady is drawn in the frenzy of dance. You can almost hear the music of this scene. The lady shown is Louise Weber — a famed dancer who performed under the stage name 'La Goulue'. Her nickname — meaning 'the glutton' — came from her appetite for food and alcohol and, during the 1880s and 1890s, she was the undisputed queen of Montmartre nightlife.

The image is instantly clear yet it has an unusual composition. Lautrec played with perspective and cleverly abstracted many of the scene's unnecessary details. It catches your eye but then begs for you to look at it a little longer. The illustrator had a natural understanding of the principles of what a poster could do, and the intent for this work couldn't be clearer. La Goulue's provocative pose, her lifted dress and the image's unusual and distinct viewpoint all clearly embrace the hard truth that sex sells. His image is brash, provocative, erotic and vulgar. It is — as his friend Thadée Natanson described it at the time — a “fist in the face”.

Lautrec's success brought him much acclaim, and he produced several other works for the venue. He continued to be a patron and knew the other regulars and entertainers. He produced many great paintings of life at the Moulin Rouge too. These artworks embrace the debauchery of the lifestyle and present it raw with no judgement or criticism.

Lautrec completely immersed himself in the world that he illustrated. His dedication to this lifestyle left us with an amazing visual account of life during this period of history. Tragically, this type of living took its toll and, in 1901, Lautrec died at the age of just thirty-six. His career had lasted a little over a decade. Yet, during this time, he played a vital role in the history of art and illustration.

Before Lautrec, posters typically conveyed their messages with words. He proved that pictures could be a far more powerful and effective means of communication. In doing this, he formed the basis of what would develop into our current compulsion for advertising and consumer culture. While it may not have been the legacy he intended — it is only one part of his contribution to our culture. His illustrations brought the language of the avant-garde to the general public, and his posters helped elevate the importance of illustration as a medium. For that, I doff my top hat, raise a glass of champagne and fondly say merci beaucoup!

Where next?

If you found this essay interesting, you might also enjoy exploring these selections:

The Belle Époque poster art of Jules Chéret

It would be remiss to talk about Lautrec and not mention the work of Chèret (1836–1932). Known to many as the 'father of the modern poster', Chéret had been producing posters since the 1870s, and his images helped to define the vibrant spirit of the Belle Époque.

The Art Nouveau prints of Théophile Steinlen

Steinlen (1859–1923) was a painter and printmaker who produced many iconic French posters. His Cabaret Du Chat Noir print no doubt played a sizable role in the poster craze that peaked in France during the 1890s.

The advertising posters of Leonetto Cappiello

If Chéret was 'the father of the modern poster' — then Cappiello (1875–1942) was easily 'the father of modern advertising'. He was an innovator of poster design and produced over five hundred and thirty advertising posters over the course of his career.