The year is 1882. A plucky young seventeen-year-old from Leeds takes a train to London. He sports a bowl haircut and only has a sovereign in his pocket. Eager to make it in the city, he visits his aunt and uncle's home in Islington. They are not so keen to see him, but they allow him to stay the night on the sole condition that he returns home the following evening. He reluctantly agrees and spends the following day taking in the sights and sounds of the city. When evening arrives, he is placed on a train and sent back to Leeds. As soon as the train reaches its second stop, he disembarks and walks back to the city. Despite having nowhere to stay and hardly any money to his name, he is determined to make it in London. His name is Phil May (1864–1903), and he will eventually go on to be known to many as the 'grandfather of British illustration'.

Born in Leeds in 1864, May's father died when he was just nine. He grew up in poverty, and his family struggled to survive. As a boy, he spent time working in a theatre, and it was there that he often got to sketch the actors' portraits. Poverty was hard, and May tried to find income through a number of jobs. His early career saw him undertaking clerical work at a solicitor's office. He also did timekeeping at a foundry and even acted on the stages of Scarborough and Leeds. Despite his poor background, May knew that he was destined to become an illustrator.

Convinced that London was where he would find his success, he made it his goal to move to the city. He once wrote that “if a man really has any originality in him it is bound to find its way out”. In those days, there were very few illustrated papers in circulation; and nearly all of them were based in the capital. When he travelled to London in 1882, he had no luck in finding work. He begged for food at public houses and drank water from street fountains. Too proud to return to his aunt and uncle's home, he slept in parks and old market carts. He had no friends in the city and no introductions into the industry. Unlike other illustrators at that time, May had no formal art training. “I never had a drawing lesson in my life,” he said, “but I can’t remember a time when I didn’t draw”.

Fortunately, May's determination paid off, and he eventually managed to pick up a few small jobs. One led to an introduction to the management of a relatively new political magazine called the St. Stephens Review. When May was first introduced to them, the magazine was not illustrated, but they had plans for a special illustrated Christmas edition. May was excited by this news and felt that his luck was about to change but, unfortunately, it wasn't that simple. The magazine had already arranged for another illustrator to do the job. May was crestfallen. His time of living rough on the streets had taken a toll, and his health was poor. Unwell, unemployed and still homeless, he reluctantly returned to Leeds.

Upon returning home, May found a telegram waiting for him. The illustrations that had been submitted to the St. Stephens Review had been unsuitable for publication, and they now wanted him to work on new ones. It was a big job that included cartoons, a cover and initials. May was undeterred. With only a week to complete the task, he returned to London and quickly rented a room in a small hotel. He worked day and night, churning out every illustration that the magazine requested.

The St. Stephens Review was impressed. They loved the illustrations and published them with pride in their Christmas edition. In fact, the Review was so impressed with his work that they decided to continue to have illustrations in all their regular issues too. They asked May to join their staff and — as the saying goes — the rest was history.

Things continued to go from strength to strength for May. He spent time in Australia, Rome and Paris and worked for such publications as The Sydney Bulletin, Punch, and The Graphic. May had a reputation for his images of London street life, and he captured this aspect of society with compassion and kindness. That said, May was also a man of his time, and many of his cartoons have now aged poorly. In his day, racism, misogyny and anti-Semitism were all acceptable subjects for humour. By today's standards, many of these cartoons feel horribly offensive.

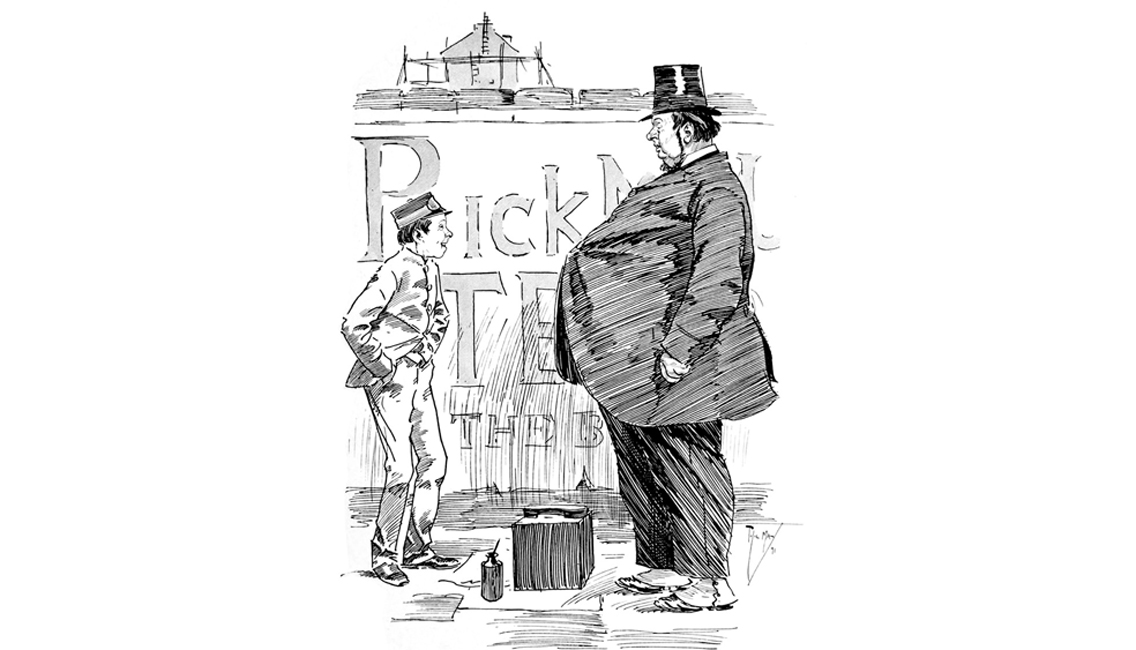

That said, when viewing any work from the past, we need to attempt to view it objectively. There is plenty to love in May's illustrations, and a surprising number of his jokes still stand up. Prior to May, cartoons had been long and drawn out things. This example by William Thackeray from 1848 is somewhat indicative of the types of cartoons that were being produced. Unlike the snappy one-liners that we're familiar with today, text was nearly always central to Victorian cartoons; and the illustrations often struggled to correspond with everything that was mentioned in the caption.

May's work demonstrates the illustrator's keen ability for combining beautifully elegant black-and-white illustrations with short and witty captions. The cartoons featured in this essay are all taken from The Phil May Album (1900) — one of May's most successful books. His work was immensely popular, and he produced a large number of annuals and collections. The Phil May Album is a wonderful introduction to his illustrations, and it features one hundred and twenty cartoons in total.

In his lifetime, May went from being a poor, anonymous, and untrained illustrator, to a widely recognised and much-loved cartoonist. He is exemplary of the Victorian aspiration for becoming a self-made man. Today, his work stands as a lasting example of the moment when the overly-detailed Victorian style of illustration was replaced with an economic line and a lightness of touch. Through the work of May, we can see a new generation of modern cartoons being born and — if the humour takes us — we might even get a handful of chuckles along the way!

Where next?

If you found this essay interesting you might also enjoy exploring these selections:

Tom Browne's work in Dan Leno's Comic Journal

From 1898 to 1899, Dan Leno's Comic Journal presented comic tales featuring Dan Leno (1860–1904). Leno was a real-life figure in comedy and theatre. The comic paper was frequently illustrated by Tom Browne (1870–1910) — whose contribution to the history of British comics goes arguably unequalled.

Rossetti and His Circle by Max Beerbohm

If you enjoy May's economy of line, then you will almost certainly enjoy the the work of Max Beerbohm (1872–1956). Rossetti and His Circle (1922) is often considered to be Beerbohm's masterpiece. It offers a great introduction to the work of this English caricaturist, essayist and parodist.

The War Cartoons of David Low

Another self-taught cartoonist, David Low (1891–1963), was heavily inspired by the work of May. Best known for the political cartoons he produced during World War II, his work earned him a place on the Gestapo's death list. His book Years of Wrath – 1932-45 is a must for any cartoon fan.