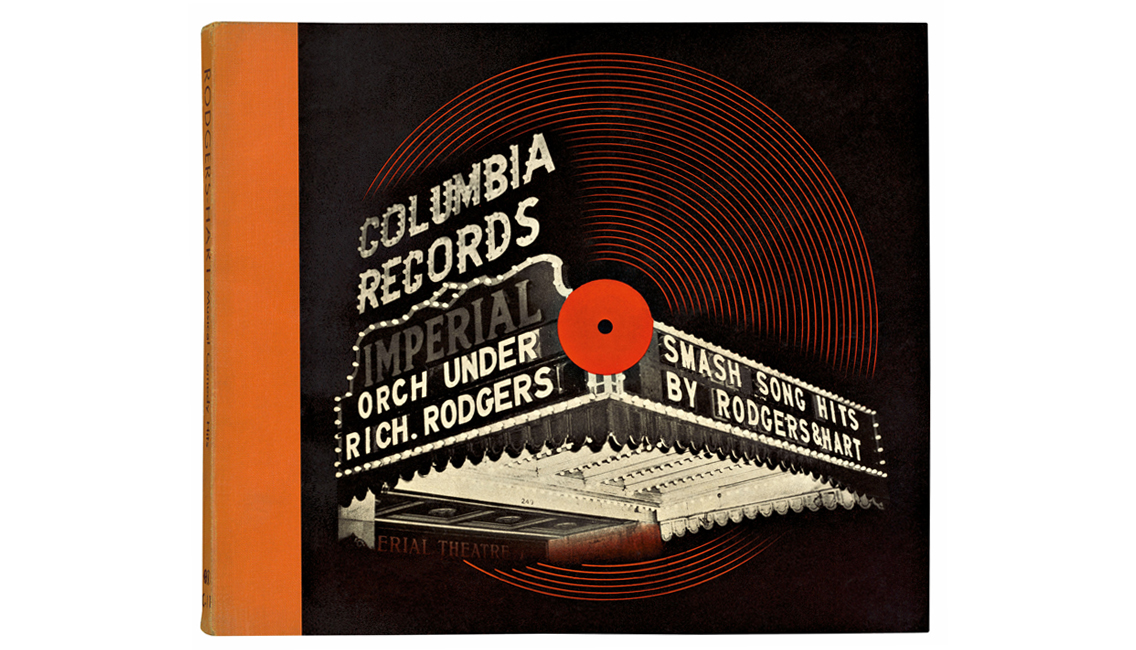

In 1939 a twenty-three-year-old Alex Steinweiss (1917–2011) was working at Columbia Records when inspiration struck. He quickly grabbed a photographer, and the pair headed down to New York's West 45th Street and stood outside the city's famous Imperial Theatre. Looking up at the building's distinctive marquee, they both agreed — it was perfect!

The young Steinweiss had only just landed a job at Columbia Records where he worked as the label's first art director. CBS had recently opened a new headquarters in Bridgeport, Connecticut and their advertising manager was eager to hire someone to design promotional displays and advertisements for the label. It was a dream job, but Steinweiss already had greater things in mind.

At the Imperial Theatre Steinweiss convinced the owner to briefly change the signage of the marquee. As evening arrived, they swapped out the letters and then lit them up: 'Smash Song Hits by Rodgers & Hart', it proudly announced. The photographer snapped a picture and, in doing so, he captured a little bit of history. This image would go on to become the world's very first album cover.

These days, we tend to take album artwork for granted, yet before Steinweiss, the record industry really didn't have much of a graphic tradition. When the 78 RPM emerged during the 1910s, they were all sold separately. Each record would last just three to five minutes, and each one was typically packaged in dull paper or cardboard sleeves that either had the name of the producer on it or the name of the retailer who was selling it.

By the 1920s, record labels began to offer special 'record albums'. These were dark-coloured books with leatherette bindings and empty sleeves (quite similar to photo albums). A record album would offer more protection for a collector's records and allow for them to build a personal record collection. By the 1930s, some record companies were expanding on the album idea by issuing specially pre-assembled albums. These albums could include recordings from a particular artist, a genre, a suite of classical music, or even a hits compilation. Despite this novel idea, all of these collections generally looked the same and offered very few visual clues to help consumers tell each one apart.

“To my mind, this was no way to package beautiful music,” Steinweiss remarked in the fantastic book Steinweiss: The Inventor of the Modern Album Cover. For him, these indistinguishable covers had to change. Eager to do something about it, he walked into management and insisted that they adopt a new way to sell records. Initially, Columbia was reluctant to get on board (a $2,500 investment for Steinweiss' idea was certainly a lot to ask for) yet, when they did eventually give in, record sales increased by almost nine-hundred percent, and the idea was quickly heralded as an indisputable success.

Throughout the forties, Steinweiss’ work dominated the world of music. Records, that had typically been sold at the back of appliance stores, had become desirable objects that could capture the imagination (and wallets) of music lovers everywhere. From jazz bands to show tunes and from classical works to pop acts, Steinweiss – quite literally – covered them all. “I love music so much," he said in the 2009 book, "and I had such ambition that I was willing to go way beyond what the hell they paid me for. I wanted people to look at the artwork and hear the music.”

For Steinweiss, album artwork offered the complete package. He approached each and every album like a small canvas. For him, they were opportunities for experimentation and, every day he'd play with layout, illustration, colour, typography and hand-lettering. His real talent lay in his ability to combine all these unique elements effortlessly and fluidly. With a Steinweiss cover, you were nearly always guaranteed to see modern elegant type, rich and vibrant colours and beautiful lively illustration.

Sometimes his work could be highly symbolic or conceptual — such as his striking illustration for Paul Robeson's 1942 Songs of Free Men (featured earlier in this post). Other times, Steinweiss could be lighthearted and whimsical; his cover for Robin Hood (above) demonstrates this particularly well. No matter the record, its content was always the starting point and, as a music fan, that made his life a joy.

From 1938 until 1973 Steinweiss worked actively in record cover design. Following his run at Columbia, he went on to design packages for London, Decca and Everest Records. During the course of his career, he produced nearly two-and-a-half thousand covers and created nearly every one of them by hand.

Following the forties and fifties, modernism eventually gave way to psychedelia, and the emerging youth culture of the sixties quickly became the prime market for the cash savvy record executives. While these album covers feel distinctly removed from the work of Steinweiss (one such example will be our focus next time), they do owe an incredible debt of gratitude to Steinweiss's legacy.

While Steinweiss may have given us the very first album cover – in many ways – his legacy is even greater than this. Steinweiss left us with the blueprint for what an album cover is and what it can be. As legacies go, that ain't too bad!

Where next?

If you found this essay interesting, you might also enjoy exploring these selections:

Jim Flora's lively jazz covers of the 40s and 50s

In 1942 Steinweiss recruited Jim Flora (1914–1998) to handle the jazz covers at Columbia. Flora was a huge jazz fan, and his comical and idiosyncratic illustrations brought vigour and energy to the music of the era.

The graphic modernism of Saul Bass' album covers

Best known for designing some of the most iconic title sequences in the history of cinema, Saul Bass (1920–1996) also created a number of album covers. Alongside artwork for film soundtracks, Bass also created covers for jazz records, musicals and even a record of tone poems conducted by Frank Sinatra.

The modern-art influenced jazz covers of Neil Fujita

A talented book and record cover designer, Columbia hired Neil Fujita (1921–2010) in 1954 to build on the work of Steinweiss. During this time he created iconic work including covers such as Miles Davis' 'Round About Midnight (1959), Dave Brubeck's Time Out (1959) and Charles Mingus' Mingus Ah Um (1959).