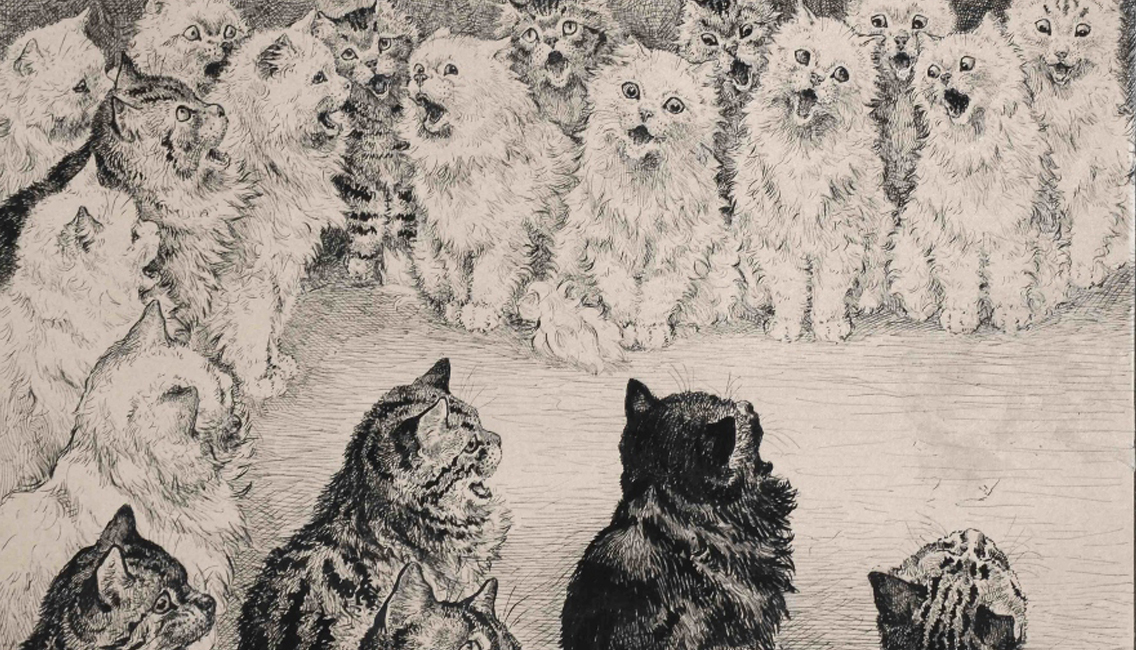

Louis Wain was one of the most popular commercial illustrators in the history of England. Born in 1860, his anthropomorphic portrayals of cats captured the imagination of the Edwardian era, and his work helped to elevate the profile and popularity of our feline friends to unprecedented heights. Before Wain, cats in England were often thought of with contempt, but his work humanised them and helped to show them as something to be liked, admired and even loved.

His illustrations were so popular that throughout the beginning of the twentieth century, most homes had at least one of his famous cat annuals and many nurseries had Wain posters hanging on their walls. “He made the cat his own” H.G. Wells once remarked. “He invented a cat style, a cat society, a whole cat world.”

Today, his work continues to attract interest, but his legacy is based more on his struggles with mental health than the work that he created. While never officially diagnosed with schizophrenia, many people believe that he suffered from this condition, and some have argued that his later drawings demonstrate his psychotic deterioration. While this is certainly a fascinating aspect of his work, it is only one part of a greater story; we should be careful not to allow it to overshadow the fascinating work he created during his lifetime.

Surprisingly, Wain never started out wanting to be a cat illustrator. Early on in his career, he had felt that nobody would take him seriously if he just drew pictures of cats, and so his initial ambition was to be a press artist. In his early years, he specialised in drawing animals and country scenes, and he had work published in several journals, including the popular Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News.

It wasn’t until 1884, when Wain was twenty-four, that he sold his first drawing of a cat to The Illustrated London News. Two years after this, he got his first real taste of success when he was commissioned to illustrate a children’s book for Macmillan called Madame Tabby's Establishment (pictured above). Written by Caroline Hughes (under the pen-name Kari), his illustrations seem a lot more traditional and sober when compared to his later work. Yet even in these early examples, we can see signs of his ability to give a cat a personality and a playful nature.

Despite the happiness seen throughout his work, the tale of Wain’s interest in cats is sadly a tragic one. In 1883 Wain married Emily Richardson. Not long after the couple wed, Emily became unwell. Over the course of her prolonged illness, the illustrator sketched their cat as a way to keep her spirits up. She must have been delighted when, in the Autumn of 1886, she saw their cat depicted in Kari’s book. There must have been even more reason for joy when a few months later Wain was commissioned again by The Illustrated London News to draw more illustrations based on their cat. His work, ‘A Kitten’s Christmas Party’ was hugely popular and a great success. It set Wain on the road to artistic and commercial greatness, but, sadly, he was unable to enjoy this accomplishment as – a few months later – Emily passed away.

The effects of this tragedy had a huge impact on Wain, and he became increasingly more inward-looking. As his success went from strength to strength, he continued to struggle with anxiety and depression, and despite his professional accomplishments, his personal life was never quite the same again.

Looking back at his work now, it may be possible to read some of this sadness in his early illustrations, but perhaps I am simply projecting. Either way, his cat illustrations certainly tapped into something that resonated well with the people of the time. Often playfully poking fun at Edwardian trends – his cats could play golf, be mothers, drink tea, smoke cigarettes and go to the opera. They weren’t social satires per se, but they certainly had fun in highlighting the topical trends of the time. Wain’s illustrations have a sardonic sense of humour, and the human-like expressions of his creatures continue to amuse and entertain.

As an illustrator, Wain was hugely prolific. A regular contributor to British magazines and newspapers, his images populated many of the era’s most loved children’s books and postcards. During the 1900s, Wain was producing on average six hundred new designs every year, and his annual output of cats could reach up to one-and-a-half thousand. In his lifetime, he illustrated more than two hundred books and had sixteen hugely successful Christmas annuals.

For a brief period, he even branched out into ceramics – creating a collection of bizarre and brilliant futurist cats. Wain was much loved and could easily be considered a celebrity of his day. He became known as a leading authority on all things cats and was elected president of the National Cat Club. He judged cat competitions and was involved in several animal charities. All of this helped to bolster the country’s love and appreciation for the domesticated cats, but it wasn’t just England that fell for Wain’s charms. He also had considerable success in America and, between 1907 and 1910, he contributed a cartoon strip at Hearst's New York Journal-American. Tragically this was to be his last regular job.

Wain lacked a sense of business acumen and was often exploited. A lot of the time, he sold his work outright and never asked for publishing royalties. By the time the war broke in 1914, Wain found himself struggling to find a market amid the wartime paper shortage. By the 1920s, he was in poverty. His depression continued, and his mental health deteriorated. Often known to strike out in violent and erratic ways, he was eventually committed to the pauper ward of London’s Springfield Mental Hospital in 1924.

In those days, the understanding of mental health was primitive at best. We have no way of fully understanding, or even knowing, exactly what Wain was suffering from. The culture at the time simply sent anyone who had a mental illness to the asylum.

During this period, Wain continued to draw cats. Some of these became more and more abstract – often reaching a point where their features were nearly impossible to identify. Were these drawings the product of schizophrenia, or were they merely an artist experimenting with a new style? Could Wain have suffered dementia, or did he have Asperger’s Syndrome? We’ll probably never know the full answer for sure, but one thing we can all agree on is that the work is fascinating to look at. Each drawing seems to have a certain coherence, and Wain has a brave sense of experimentation and vibrant use of colour. They’re all beautiful drawings to look at.

One thing that is often overlooked is the fact that Wain also continued to produce work in a more traditional style during this time too. The belief that his abstract drawings demonstrate the progressive deterioration of his mental state is quite likely a falsehood – the result of a claim made in a book called Psychotic Art that was published in the 1960s. All art should be considered as an expression of the artist, and Wain’s progression into psychedelia is just one aspect of his creative identity. Whether or not that aspect was triggered by mental illness is a moot point. What we do know is that Wain had a difficult life; and that he spent much of his time making some amazing, some curious and some fascinating illustrations.

For me, Wain’s most affecting image is not one of his more abstract works. It is, in fact, quite a modest piece that at first looks somewhat unassuming. Made in chalk and ink, it shows a small and cheery cat who stares out from the page with a broad and jolly grin. Underneath is written: “I am happy because everyone loves me”. It aims at positivity, but there is an unavoidable sadness to it. Made while Wain was in care, it is arguably the illustrator’s most revealing work – capturing the despair in his life and highlighting his tragic struggle for happiness.

Wain would spend the remaining fifteen years of his life in institutional care. Initially, many of his friends and admirers didn’t know of his incarceration. But, when his situation was discovered in 1925, his circumstances were publicised widely. A public appeal was made that eventually raised £2,300. After a personal intervention by Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, the money was able to send Wain to the Bethlem Royal Hospital – one of the better hospitals of the time. In many ways, it was a small gesture for a man who had given the world so much happiness but hopefully, it made his final years a little easier.

The life and work of Louis Wain is a story of contradictions. His work seems happy, and yet his life was tragic. His cats seem playful, and yet they are also seem unsettling. Should his work be viewed as an expression of the artist, or should we choose to view it as an expression of an illness? Did his condition open him up to a world of colours and shapes, or were those things already deep inside him? Who knows. We could easily spend a day debating on how and why these images were made, but what really matters is the fact that they were made and, for many people, they brought great happiness and entertainment. Hopefully, that was something that Wain himself could recognise and, hopefully, that offered him some small sense of comfort during his difficult life.

Where next?

If you found this essay interesting, you might also enjoy exploring these selections:

Gottfried Mind: The Raphael of Cats

Swiss artist Gottfried Mind (1768–1814) had a special talent for drawing cats. Born autistic, Mind's teachers found he was incapable of meeting the demands of school work but recognised his artistic potential and encouraged him to pursue a career as an artist. Mind had a great fondness for cats and spent much of his time with them. His ability to depict them in such a realistic manner earned him a reputation as 'The Raphael of Cats'.

The Mainzer Cat Postcards

Another Swiss artist who loved cats was Eugen Hartung (1897–1973). A popular children's book illustrator in his native Switzerland, Hartung is possibly best known for the postcards he illustrated for the Alfred Mainzer Company. Often depicting comical scenes with anthropomorphised cats, his images were hugely popular during the 1950s.

Mental Health and Art

Art and mental health have always had a relationship with examples from people like James Tilly Matthews (1770–1815) to contemporary people like the musician and artist Daniel Johnston (1961). In 2013, the BBC's Imagine presented a fascinating documentary on the subject called 'Turning the Art World Inside Out'. If you can track down a version of it, I highly recommend you give it a watch.